There can be no equivocation for Nigeria

Debunking the “Farmer-Herder” Myth: The Systematic Targeting of Christians in Nigeria’s Hidden Genocide

(Washington, DC) — In recent weeks, prominent figures have perpetuated a narrative that downplays the religious dimensions of violence in Nigeria, framing it instead as mere social or economic clashes between farmers and herders and falsely arguing that more Muslims are killed than Christians. This portrayal not only misrepresents the data but also obscures the disproportionate suffering of Christian communities at the hands of the Fulani Ethnic Militia (FEM) in Nigeria’s forgotten Middle Belt states.

“On average, 2.4 Christians were killed for every Muslim, with Christians murdered at a rate 5.2 times higher than Muslims relative to population size in affected states. We must be very clear. There can be no equivocation. Nigeria’s Christians are facing genocidal violence from multiple terror groups while their own Muslim-dominated government ignores and denies their plight, routinely fails to arrive in time, make arrests, or prosecute perpetrators,” says Dede Laugesen, president of Save the Persecuted Christians, a U.S. religious freedom watchdog advocating for Christians in Nigeria.

“The driving force behind the murder, hostage-taking, and other extreme abuse facing Nigerian Christians is Islamic jihad perpetrated by multiple terror groups in competition with one another, including the Fulani Ethnic Militia in the Christian Middle Belt States. You cannot separate religion from jihad, and yes, moderate Muslims are sometimes killed and taken hostage alongside their Christian neighbors. Their experience doesn’t begin to equate to over 300 Christian communities decimated and occupied with impunity by Muslim terrorists, resulting in some 4-12 million internally displaced, which I personally witnessed in January 2023, when I visited the most impacted Nigerian states—Plateau and Benue—where diplomats and bureaucrats refuse to go. Nor does it address the 19,100 churches destroyed by violence since 2009. Nigerian Muslims are not suffering large-scale, targeted attacks daily as are Nigerian Christians,” Laugesen added.

Drawing on rigorous documentation from the Observatory for Religious Freedom in Africa (ORFA), this article dismantles these claims, revealing a pattern of ethnoreligious terrorism that has claimed tens of thousands of lives while evading global scrutiny.

High-level acknowledgments, such as President Donald J. Trump’s address to the United Nations General Assembly on September 23, 2025, underscore the urgency: “Let us defend free speech and free expression. Let us protect religious liberty, including for the most persecuted religion on the planet today. It’s called Christianity.”

Misleading Narratives from Influential Voices

Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, recently addressed the violence against Christians in Nigeria. He described the situation as “not a religious conflict, but more a social conflict, for example, between herders and farmers.” Parolin emphasized that “many Muslims are also victims of this intolerance” and that extremist groups “use violence against all those they consider opponents, without distinction.” While acknowledging the complexity, his comments align with a broader tendency to generalize the violence, suggesting parity in victimhood and downplaying targeted persecution.

Similarly, Massad Boulos, described in some reports as a US envoy (though he serves as Donald Trump’s senior adviser on Arab and African affairs), countered claims of Christian genocide in Nigeria. In a video statement, Boulos asserted that “Boko Haram and ISIS [are] killing more Muslims than Christians” and that “people of all religions are dying as a result of terrorist acts.” He framed incidents in Nigeria’s Middle Belt as clashes where “farmers happened to be Christian and some herdsmen going through” led to conflicts, insisting it’s “not something that we can say specifically targeted about this specific group.” Boulos further claimed Nigeria has lived in “harmony for four centuries” with a 50-50 split between Christians and Muslims, dismissing serious religious issues.

And, U.S. Ambassador to Nigeria Richard Mills has also cautioned against framing terrorist attacks in the country along religious lines, saying victims of insurgency and violence cut across faiths, tribes and regions, and there are more Muslim victims than Christian.

These statements, echoed in Nigerian and international outlets, promote a false “farmer-herder” clash narrative that critics argue is a form of propaganda, parroted ad nauseam by lobbyists paid by the Nigerian government, meant to deflect from the Islamist underpinnings of the violence.

However, independent data paints a starkly different picture, exposing these claims as misinformation that ignores the scale and intent behind the attacks—attacks that align with global patterns of Christian persecution, as highlighted by President Trump in his UNGA speech.

The Reality: Data-Driven Evidence of Disproportionate Christian Targeting

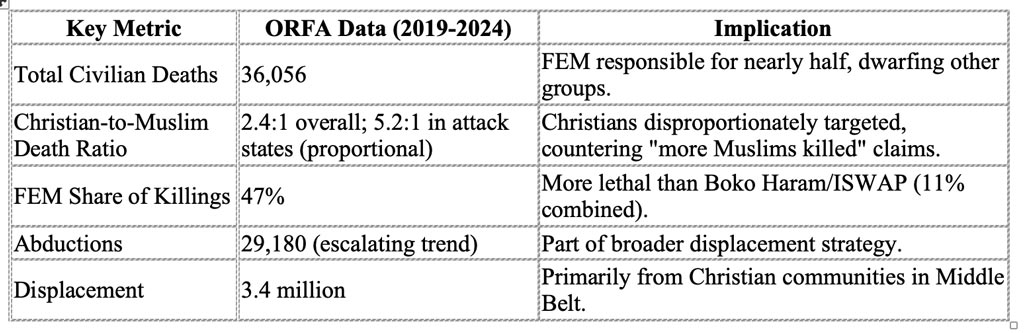

ORFA’s comprehensive analysis from October 2019 to September 2024 reveals a crisis far removed from benign “clashes.” The organization documented 66,656 total deaths, including 36,056 civilians, across 13,437 incidents of extreme violence. Contrary to claims of equal victimhood, 2.4 Christians were killed for every Muslim, with Christians murdered at a rate 5.2 times higher than Muslims relative to population size in affected states. This disparity directly contradicts assertions like Boulos’s that more Muslims are killed or Parolin’s implication of indiscriminate violence.

The perpetrators tell an even more damning story. FEM accounted for 47% of civilian killings—over five times the 11% attributed to Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) combined. While jihadist groups like Boko Haram grab headlines with spectacular attacks, FEM’s operations are systematic and territorial, with 79% of civilian deaths occurring in land-based invasions of small Christian farming settlements involving killing, rape, abduction, and arson. These are not random herder-farmer disputes but coordinated efforts to achieve demographic change and control in Nigeria’s Middle Belt.

This table underscores how the violence extends beyond deaths to forced displacement and economic destruction, threatening Nigeria’s food security as Christian agricultural heartlands are depopulated.

Patterns of Atrocity: Beyond “Clashes” to Targeted Terror

The “farmer-herder” label conveniently masks the ethnoreligious motivations evident in attack patterns. ORFA notes that FEM invasions focus on Christian settlements in the North Central Zone (Christian Middle Belt) and Kaduna state, with 3,776 killing incidents and 1,990 abductions documented—mostly by FEM. High-profile massacres illustrate this intent:

- Agatu Massacre (February-March 2016): 300-500 killed in Benue State, marking early large-scale FEM coordination.

- Christmas Eve Massacre (2023): Between 200-500 lives lost in Plateau State’s Bokkos area, timed for maximum psychological impact on Christians.

- Yelwata Massacre (June 13-14, 2025): More than 270 slain, mostly women and children, in Benue State’s Guma area.

These events follow a consistent strategy: nighttime raids on sleeping villages, selective targeting during Christian holidays, and no equivalent attacks on Muslim communities. This is not mutual conflict but a “slow-motion genocide,” as ORFA reports, reshaping Nigeria’s geography through terror.

Why the Misinformation Persists and Its Dangerous Consequences

The escape of FEM from global terrorism indices, like the Global Terrorism Index (GTI)—where they ranked fourth deadliest in 2015 but vanished thereafter—stems from this misframing as “ethnic clashes” rather than terrorism. Databases prioritize “spectacular” acts, undercounting systematic raids. As a result, billions in international aid target Boko Haram/ISWAP, while Middle Belt victims receive scant support, allowing FEM to operate unchecked.

The Nigerian government is implicated in paying journalists to suppress reports of violence against Christian communities and often fails to file official security incident reports, further hindering accurate reporting. Nigerian police are federalized and citizens are forbidden from owning anything but the most primitive guns for hunting. When the terrorists descend en masse, shouting in Fulfide, “Alahu Akkbar,” local, mostly unarmed, village security volunteers are often the ones arrested simply for attempting to defend their homes, families, and neighbors, while the well-armed terrorists go free.

Statements from figures like Parolin, Boulos, and Mills, whether well-intentioned or influenced, perpetuate this invisibility. By emphasizing “social conflicts due to climate change” and “more Muslim victims,” they align with narratives that Laugesen labels as propaganda: “The Nigerian government is doing all it can to stop and suppress the truth. Truth Nigeria’s reporters, the brave on-the-ground journalists bringing us the news of hostage camps near military installations, are in danger in Nigeria because they are being surveilled and threatened by the Nigerian government for telling the truth.”

She further warns, “If no official report is filed on attacks happening in the Middle Belt, nothing happens. If the Nigerian government pays off the Nigerian media to suppress these reports, the international media will not hear about it, and neither will the State Department.” The reality, substantiated by ORFA’s data, demands a Country-of-Particular-Concern designation per the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act.

“The evidence is clear,” says Laugesen. “The Nigerian government is tolerating, likely enabling, multi-front, targeted ethnoreligious violence by Islamist militias, not equitable herder-farmer disputes—a point echoed by President Trump at UNGA, where he urged nations to ‘protect religious liberty, including for the most persecuted religion on the planet today. It’s called Christianity.’”

What is the CPC Designation for Nigeria?

Laugesen has been vocal about the need for Nigeria’s redesignation as a Country of Particular Concern by the U.S. State Department: “We were successful in getting Nigeria designated as a Country of Particular Concern under the first Trump administration but the Biden administration pulled back that designation for political reasons, and we are still waiting for that redesignation to happen, so that the Trump administration has the tools that it needs to hold Nigeria accountable.”

In September, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) introduced a bill that would mandate a “Country of Particular Concern” status for Nigeria. Earlier this year, Rep. Chris Smith (R-NJ) introduced a resolution calling on Congress to acknowledge their opinion that Nigeria ought to be so designated.

The International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) of 1998 (22 U.S.C. § 6401 et seq.) requires the U.S. President (typically delegated to the Secretary of State) to annually review the status of religious freedom in every foreign country. A country is designated as a CPC if its government engages in or tolerates “particularly severe violations of religious freedom” during the preceding 12 months (or since the last review, if longer). These violations are defined as systematic, ongoing, and egregious, including:

- Torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Prolonged detention without charges.

- Causing the disappearance of persons through abduction or clandestine detention.

- Other flagrant denials of the right to life, liberty, or security of persons based on religious belief.

The President must also identify responsible government agencies, instrumentalities, or officials for targeted actions. Designations are reported to Congress within 90 days, including any actions taken. A CPC designation can be removed if the President determines the violations have ceased or substantial steps have been taken to end them, with notification to Congress.

Amendments, particularly the Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act of 2016, expanded IRFA by adding a “Special Watch List” for countries engaging in or tolerating “severe” (but not “particularly severe”) violations, and “Entities of Particular Concern” for non-state actors committing similar acts. However, the core CPC criteria remain unchanged.

Upon CPC designation, the President must take one or more “commensurate” actions (proportionate to the violation’s gravity) from a specified menu under 22 U.S.C. § 6445, or equivalent substitutes, after consulting with relevant U.S. agencies and fulfilling diplomatic consultation requirements. These actions aim to promote religious freedom and can include:

- Diplomatic Measures: Private or public demarches, public condemnations (unilaterally or in multilateral forums), delaying or canceling scientific/cultural exchanges, or denying/delaying official visits.

- Economic and Financial Sanctions: Withholding U.S. funds benefiting the responsible entity; suspending development or security assistance (in whole or in part); directing U.S. representatives in international financial institutions (e.g., World Bank, IMF) to oppose loans; prohibiting U.S. Export-Import Bank agreements, loans from U.S. financial institutions, or government procurement from the entity; reducing overall U.S. assistance levels; or imposing broader sanctions under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA).

- Targeted Sanctions on Individuals: Applying visa bans, asset freezes, or other penalties on specific officials or parties responsible for the violations.

- Diplomatic Downgrades: Reducing the level of U.S. diplomatic relations.

In lieu of these, the President may negotiate a binding agreement with the foreign government to cease or substantially address the violations, which waives other actions if implemented. Exemptions or waivers are possible if violations have ended, if it furthers IRFA’s purposes, or if required by vital U.S. national interests, but must be justified in a report to Congress. Actions cannot terminate or limit U.S. development or agricultural assistance under certain laws, and CPC countries are ineligible for specific aid programs.

These tools provide diplomatic, economic, and targeted leverage to pressure CPC governments, though implementation varies based on U.S. interests and waivers.

This designation would provide diplomatic leverage to address the unchecked violence and ensure accountability, particularly given recent U.S. arms sales to Nigeria—$346 million approved in August 2025 and $997 million in 2022—despite concerns over human rights abuses and corruption. Laugesen cautions, “The United States must ensure that the over $1 billion in arms sales approved for Nigeria does not further equip the terrorists, nor the corrupt military industrial complex that ensures the violence never ends.”

A Call for Accountability and Reform

Nigeria’s crisis requires urgent reevaluation. International bodies must reform monitoring to capture all forms of religious-based violence, regardless of labels. Diplomatic pressure should focus on FEM as a terrorist entity, with aid redirected to protect vulnerable Christian communities. Ignoring the data risks not just lives but the stability of Africa’s most populous nation.

The evidence is clear: the “farmer-herder” narrative is a myth that shields perpetrators. It’s time to confront the facts and act to designate Nigeria before more communities vanish, heeding calls like President Trump’s to safeguard Christianity as the world’s most persecuted faith.

“For President Trump, this is an opportunity. In his second term, he has stopped eight wars,” said Laugesen. “If he does the right thing and ignores his misinformed envoys, Trump can add to his impressive tally by stopping an active Genocide of Christians. Naming Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern and using humiliating targeted sanctions on its officials is a critical step toward meeting that noble goal.”